BrewingTravisty

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 6, 2015

- Messages

- 741

- Reaction score

- 139

When you first start researching into homebrewing (if you research like I do) you may think that beer making is a delicate process, where the wind blowing east instead of west on brew day will ruin your beer. There are many more don'ts on brewing than do's. But in reality the beauty of homebrewing is the ability to push the envelope, toe the line and bend some rules a little. Like fermenting in an air tight container.

I am one of those people that can never take any word as absolute law when it comes to most anything. If you tell me the beer must sit in primary for 3 weeks before bottling and then another 3 weeks in bottle to condition, I'm going to ferment for 1 week and bottle for a few days just to see what I get. (surprisingly I'm a very patient person.)

Sometimes my rebellious nature works in my favor, sometimes it blows up in my face but it always gives me something interesting to bore my nonbrewing friends and family with. So that's a win in my book. And yes, I have successfully went grain to glass in less than 2 weeks with bottle conditioning. And yes, they were slightly better with an extra week on top of that.

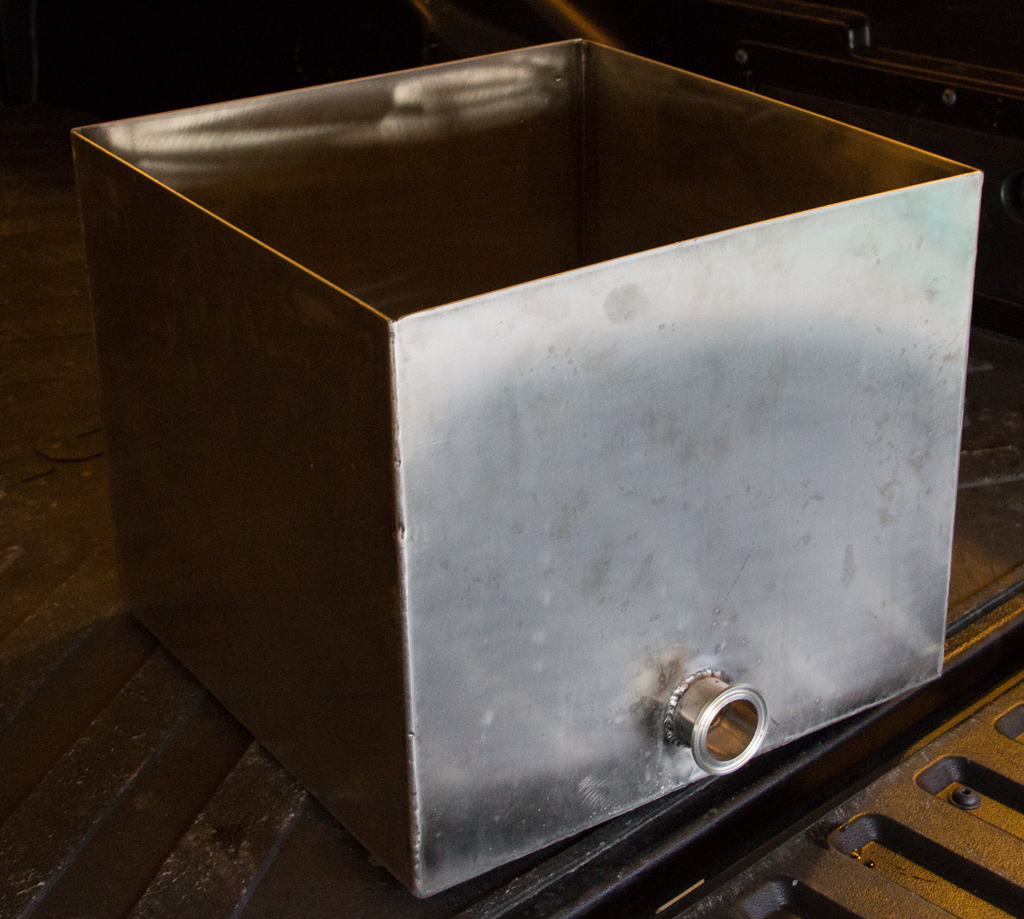

I figured that in the past it was very unlikely that brewers had air tight fermenters. Long story short I decided to experiment a bit, and not put my the lid on my fermenting bucket. Of course I did my own research to see if it's already been done and found that I'm far from a trend setter. Either way, this should be fun.

Of course, open fermentation is nothing new. It's been done for ages, and even still done by some today. It also still holds a stigma among homebrewers as one of the many "don'ts" of brewing. I want to test that stigma, and see what my results are.

Here's a picture 12 hours after pitching, in a completely open fermenter. I know, some men just want to watch the world burn.

View attachment 1449293350778.jpg

I am one of those people that can never take any word as absolute law when it comes to most anything. If you tell me the beer must sit in primary for 3 weeks before bottling and then another 3 weeks in bottle to condition, I'm going to ferment for 1 week and bottle for a few days just to see what I get. (surprisingly I'm a very patient person.)

Sometimes my rebellious nature works in my favor, sometimes it blows up in my face but it always gives me something interesting to bore my nonbrewing friends and family with. So that's a win in my book. And yes, I have successfully went grain to glass in less than 2 weeks with bottle conditioning. And yes, they were slightly better with an extra week on top of that.

I figured that in the past it was very unlikely that brewers had air tight fermenters. Long story short I decided to experiment a bit, and not put my the lid on my fermenting bucket. Of course I did my own research to see if it's already been done and found that I'm far from a trend setter. Either way, this should be fun.

Of course, open fermentation is nothing new. It's been done for ages, and even still done by some today. It also still holds a stigma among homebrewers as one of the many "don'ts" of brewing. I want to test that stigma, and see what my results are.

Here's a picture 12 hours after pitching, in a completely open fermenter. I know, some men just want to watch the world burn.

View attachment 1449293350778.jpg